6 January 2026

Ahead of publication of our Scotland’s Economic and Fiscal Forecasts on 13 January 2026 and our next Fiscal Sustainability Perspectives publication in February 2026, we are today launching a new Scottish Fiscal Commission series, SFC Insights.

Our Insights will provide brief summaries of our work and role as Scotland’s Independent Fiscal Institution.

Our first Insights discuss Scotland’s public finances in the run up to the Scottish Budget on the 13 January. Today we consider “Scotland’s governments and areas of responsibility” and tomorrow we will publish an Insight explaining the main funding arrangements for the Scottish Government. We will then publish a third insight on Thursday considering some of the tools available to the Scottish Government for managing its budget when funding and spending are different to forecast.

Every year, the Scottish Government presents a Budget which sets the level of spending for “devolved” public services, this is debated and then agreed by the Scottish Parliament. The Scottish Budget has become more complicated since the start of Scottish devolution in 1999 as extra responsibilities have been transferred from the UK to the Scottish Parliament.

In this Insight we explain the roles different layers of government play in spending money in Scotland and how this features in the Scottish Budget.

Scotland has three layers of government

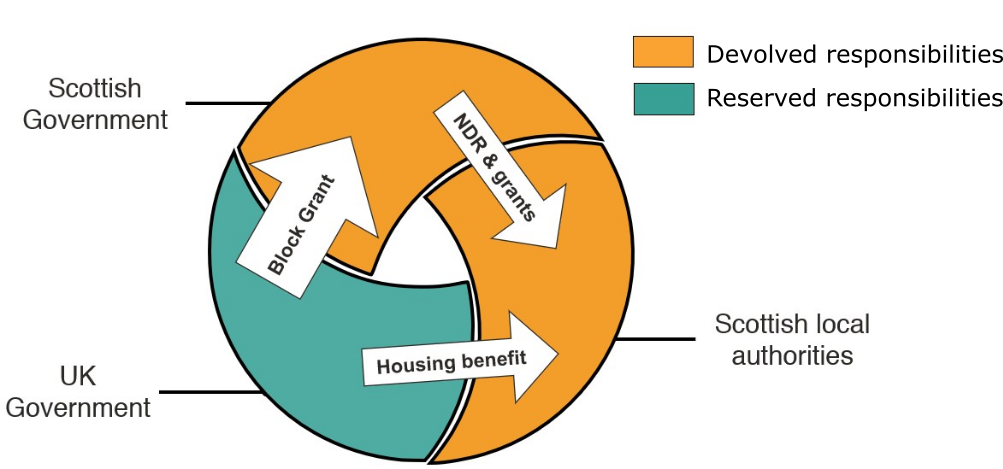

Public spending in Scotland is split between three layers of government: the UK Government, the Scottish Government and local authorities. There is a lot of interaction and overlap between these, with many transfers from one to another. For example, most of the Scottish Government’s spending is funded from a “Block Grant” from the UK Government.

Figure 1: Layers of government in Scotland

The UK Government spends directly in Scotland on reserved areas, like defence, foreign affairs and the state pension. However, most public spending is in devolved areas of responsibility, examples of which are shown below. The Scottish Government and Scottish local authorities both spend in devolved areas. The Scottish Budget sets out how the Scottish Government will allocate spending between different areas.

Scottish local authorities fund most of their spending from grants from both the Scottish and UK governments, and local taxes. Non-Domestic Rates is a Scottish Government set tax on non-residential properties, revenues are collected by local authorities, ‘pooled’ centrally by the Scottish Government and then redistributed back to local authorities as part of the Scottish Budget. Council Tax is a tax on domestic properties which is set and collected locally. Local authorities receive funding in the Scottish Budget, how that is spent is set out in each local authority’s budget, along with decisions on Council Tax.

Figure 2: Examples of devolved areas of spending

Scotland Act 2016: significant new powers devolved to the Scottish Parliament

The Scotland Act 2016 was passed by the UK Parliament. It transferred significant powers over social security to the Scottish Parliament and added to the tax powers devolved in the Scotland Act 2012.

What social security spending is devolved?

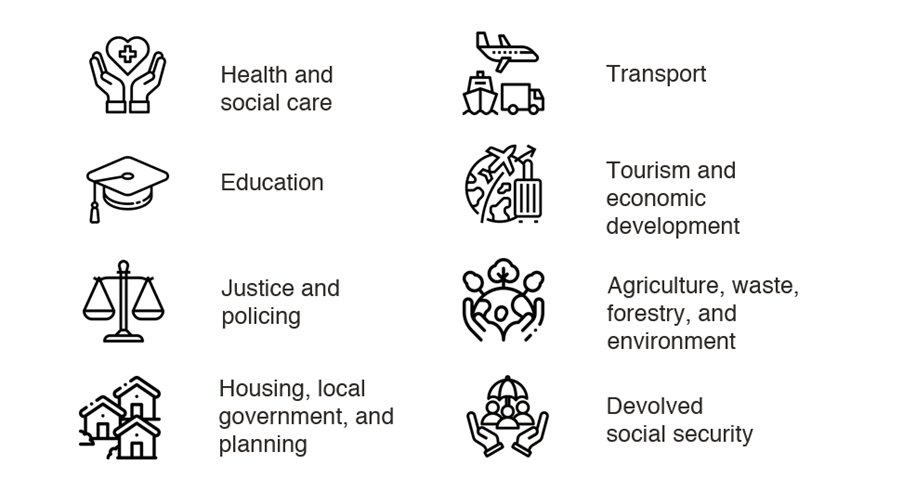

Disability and carer payments are the largest area of devolved social security spending. Benefits related to pregnancy and children are the second largest category by level of spending, and so on going up the pyramid shown below. The Scottish Budget sets out how much will be spent on social security based on our forecasts of spending.

The figure below provides examples of the Scottish Parliament’s responsibilities over social security policy. It can create new benefits that are unique to Scotland (such as the Scottish Child Payment), as long as they are in areas of devolved responsibility or designed as top-ups to existing UK Government benefits.

Figure 3: Social Security powers

What taxes are devolved?

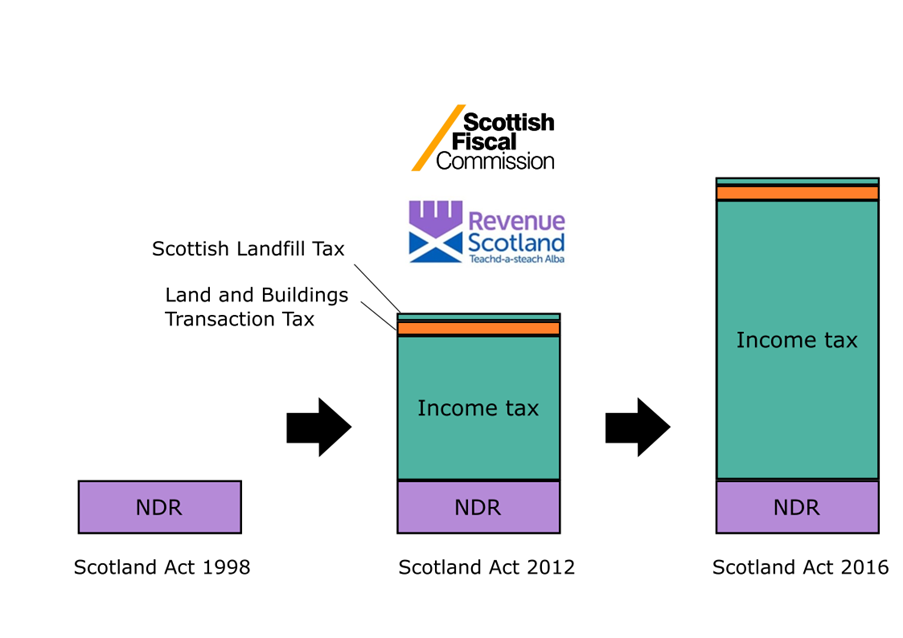

In 1999, the Scottish Budget only included one tax, Non-Domestic Rates (NDR).The Parliament also had powers to vary up or down the basic rate of income tax by up to 3p in the pound, but it never used them.

The tax powers increased as a result of Scotland Act 2012. The UK’s Stamp Duty Land Tax and Landfill Tax were devolved and replaced with Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (LBTT) and Scottish Landfill Tax (SLfT) from April 2015. The Scotland Act 2012 also devolved the Scottish Rate of Income Tax (around half of income tax revenues) which made provision for changes to income tax bands. It was only used in 2016-17 and the Scottish income tax bands matched the UK.

The Scotland Act 2016 means that since 2017-18 the Scottish Government makes more decisions on Income Tax and gets most (but not all) of the Income Tax revenue raised in Scotland. The 2016 Act also included powers to devolve or assign the revenue of more taxes. The next one to be devolved is Aggregates Levy, a charge on extracting aggregates for commercial purposes: the Scottish Aggregates Tax, which will launch in April 2026.

Figure 4: Tax powers by Scotland Act

The Scottish Budget sets out how the Scottish Government plans to use its tax powers in the next year, and how much revenue is forecast to be raised.

Next week, the Scottish Government’s Budget will set out proposals for allocating resources and raising revenues across the devolved responsibilities summarised in this Insight. This Budget will be underpinned by our forecasts for devolved tax revenues and social security spending.

Our next Insight will look at how the Block Grant to the Scottish Government is calculated and how adjustments are made to the grant that take account of the devolution of tax and social security. The third Insight will look at some of the complications that occur because tax revenues and social security payments need to be forecast before they are included in the Scottish Budget.